WHEN PROSECUTORS GET TOO CLOSE TO THE LINE

Michael Kiefer | The Arizona Republic

October 27, 2013

Noel Levy was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 1990 when he convinced a jury to convict Debra Milke of first- degree murder for allegedly helping to plan the murder of her 4-year-old son. A year later, he convinced a judge to send her to death row.

It was a scandalous case: Prosecutors charged that in December 1989, Milke asked her roommate and erstwhile suitor to kill the child. The roommate and a friend told the boy he was going to the mall to see Santa Claus. Instead, they took him to the desert in northwest Phoenix and shot him in the head.

But neither man would agree to testify against Milke, and the state's case depended on a supposed confession Milke made to a Phoenix police detective. Milke denied confessing. The detective had not recorded the interview, and there were no witnesses to the confession. When Milke's defense attorneys tried to obtain the detective's personnel record to show that he was an unreliable witness with what a federal court called a "history of misconduct, court orders and disciplinary action," the state got the judge to quash the subpoena.

"I really thought the detective was a straight shooter, and I had no idea about all the stuff that allegedly came out," Levy recently told The Arizona Republic.

But in March of this year, after Milke, now 49, had spent nearly 24 years in custody, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out her conviction and sentence because of the state's failure to turn over the detective's personnel record so that Milke's defense team could challenge the questionable confession.

The 9th Circuit put the onus on the prosecution.

"(T)he Constitution requires a fair trial," the ruling said, "and one essential element of fairness is the prosecution's obligation to turn over exculpatory evidence."

The 9th Circuit judges ordered that Milke be retried within 90 days or be released. The chief circuit judge referred the case to the U.S. Attorney General's Office to investigate civil-rights infringements. Under the 9th Circuit order, prosecutors must allow the detective's personnel record into evidence if they use the contested confession.

Prosecutors are responsible for the testimony of the law- enforcement officers investigating their cases. Cops and prosecutors are the good guys. They put criminals in prison, sometimes on death row. Juries tend to believe them when they say someone is guilty. They don't expect them to exaggerate or withhold evidence. They don't expect their witnesses to present false testimony.

Yet The Arizona Republic found that, when the stakes are highest, when a trial involves a possible death sentence, that's exactly what can happen. In half of all capital cases in Arizona since 2002, prosecutorial misconduct was alleged by appellate attorneys. Those allegations ranged in seriousness from being overemotional to encouraging perjury.

Nearly half of those allegations were validated by the Arizona Supreme Court. Only two death sentences were thrown out, one for a prosecutor’s tactics that were considered overreaching but not actual misconduct because a judge had allowed him to do it. Two prosecutors were punished, one with disbarment, the other with a short suspension.

There seldom are consequences for prosecutors, regardless of whether the miscarriage of justice occurred because of ineptness or misconduct.

In fact, they are often congratulated. Since 1990, six different prosecutors who were named prosecutor of the year by the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys Advisory Committee also were later found by appeals courts to have engaged in misconduct or inappropriate behavior during death-penalty trials, according to The Republic's examination of court documents.

And when prosecutors push the limits during criminal trials, whether crossing the line into misconduct or just walking up to it, there are risks: Convictions like Milke's get overturned, even if it takes 24 years, and innocent people, like Ray Krone, go to prison.

'Critical evidence'

In 1992, Levy helped send Krone to death row for a murder he did not commit. Krone's conviction and death sentence were thrown out three years later because the court had allowed Levy to present a videotape about matching bite marks into evidence that the defense had not had time to review.

Krone was dubbed the "Snaggletooth Killer" because of his twisted front teeth, and Levy found experts who said that those teeth matched bites on the victim's breast and neck.

"The State's discovery violation related to critical evidence in the case against the accused," the Arizona Supreme Court ruled when it tossed the case. "Discovery" refers to evidence that the opposing attorneys are supposed to make available to the other side before trial.

At retrial, Levy got another first-degree murder conviction for Krone, though at the second trial, Krone was sentenced to life in prison, where he spent seven more years.

In 2002, Krone was exonerated by a true DNA match; another man was convicted of the murder.

"It never came out that one expert said it (the bite mark) wasn't a match," Krone told The Republic. There were footprints that didn't match, DNA that was sketchy. And, as Krone said, other evidence was disregarded: an eyewitness account about a man seen near the crime scene who turned out to be the real killer, for example.

Krone sued Maricopa County and the city of Phoenix for his conviction and settled for more than $4 million.

Levy retired from the Maricopa County Attorney's Office in 2009 for medical reasons while in the middle of another capital murder trial with accusations of prosecutorial misconduct. That was the trial of Marjorie Orbin, who was charged with killing her husband and cutting his body into pieces, one of which was found in a giant plastic storage tub left in a desert lot in north Phoenix.

During Orbin's trial, Levy was twice accused of misonduct by Orbin's defense attorneys.

The first allegation was for denying Levy had spoken at the sentencing hearing of a jailhouse snitch who testified against Orbin, when he had. Then, Levy was accused of threatening another snitch who had recanted her story; during a break in her testimony, while the judge and the jury were out of the courtroom, he asked her and her attorney if they knew the maximum penalty for perjury, according to appeals court records.

Levy told the court that he was only "kibitzing" with the witness' attorney and not actually speaking to the witness herself.

The judge made a special instruction to the jury as a remedy, essentially telling them what had happened, and denied the motions for misconduct. Levy was stricken ill before the trial ended and another prosecutor took over. Orbin was found guilty, but the jury did not impose the death sentence.

There were no repercussions for Levy in that case, just as there were none in the Krone or Milke cases. The Maricopa County Attorney's Office refused to turn over his personnel file to The Republic, despite a request under the state's public-records laws, saying it was in "the best interests of justice."

"I just did my job, and I did it ethically," Levy said. "I'm fully aware of my ethical obligation to present evidence. It's up to the jury to make a decision."

As for how he feels now that a man spent 10 years in prison because of one of those jury decisions, Levy answered, "I don't look back and judge myself to say I did something wrong to Ray Krone.

"Did I commit some kind of sin? Should I go to confession and confess to you?"

Given great latitude

Prosecutors, not judges, not police, determine what, if any, charges to file, and they obtain indictments from the grand jury. They, more than a jury, determine whether a defendant acted in self-defense. They have enormous discretion over how the case unfolds, and judges grant them great latitude in their arguments.

"Prosecutors wield an enormous amount of power, including the ability to seek someone's death," said former Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley. "Considering the magnitude of this power, prosecutors have an obligation to exercise good judgment, and they must temper their powers with wisdom. Winning at all costs should play no role in being a prosecutor. Then and only then will justice be ensured."

But that doesn't necessarily happen, and Romley's 16-year tenure as county attorney was not free of allegations of misconduct by his line prosecutors in capital cases: Krone's and Milke's, for example. The way the justice system really works is that if you are charged with a crime, you are likely to be found guilty of something.

In Maricopa County Superior Court, for example, of 2,700 felony cases terminated in July of this year, 1,706 ended in plea agreements, according to sources. Only 2 percent of felony cases went to trial. Of the 65 trials that ended that same month, 59 ended in guilty verdicts, four in mistrial and two in acquittals.

"You indicted somebody, now you've got to win," said defense attorney and former Watergate prosecutor Larry Hammond.

"Prosecutors really don't take seriously the ministry of justice," Hammond said. "They see themselves as adversaries."

And they often fight their battles in the gray areas of the law.

On a recent afternoon, a Maricopa County Superior Court judge was talking about prosecutors.

She drew a line on the table with her finger and then placed an eating utensil there to mark the line.

"That's misconduct," said the judge, who asked that her name not be used. Judges are loath to comment on cases for ethical reasons, and because they need to remain impartial to the attorneys who come before them.

Then she placed another utensil an inch away and parallel to the first on the table.

"That's reversible error," she said, referring to the level of misconduct that can get a sentence or conviction thrown out.

She put her finger in the space between the utensils and said, "That's where a lot of prosecutors operate."

Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery had a quick counter.

"If courts are not enforcing the Rules of Professional Responsibility as they pertain to the conduct of defense attorneys and prosecutors, they are then responsible for what goes on in court," he said. "However, mere differences of opinion as to how a case should be tried cannot be the standard either."

Montgomery says he has beefed up prosecutor training to avoid misconduct and maintains an ethics committee to look into the actions of prosecutors, judges and defense attorneys alike.

"I'm trying to create an environment where prosecutors hold each other accountable," he said.

Tricks of the trade

As in any profession, there are tricks of the prosecutorial trade, ways to sway a jury without crossing the line.

You ask compound questions and then demand yes or no answers, for example. When the witness can't answer, you accuse him of being argumentative.

When the defense attorney is making a good case, you might accuse her of unethical conduct. You make objections in the same way football coaches call timeouts to slow a drive to the end zone.

And sex not only sells, it convicts.

"A good way to turn a questionable capital case into a definite capital case is to inject the sex component," said Tucson attorney Rick Lougee, "very often with little or no proof of the allegation."

You might also drag your feet on disclosing evidence and witness lists.

"Every piece of evidence is a fight, even if it doesn't matter to them," said Alan Tavassoli of the Maricopa County Public Defender's Office.

When does trickery become misconduct? The most frequently cited instances in appeals are withholding evidence that could aid the defendant, presenting false evidence, excluding jurors for racial reasons, making over-the-top statements, letting slip information that has deliberately been kept from the jury and disobeying a court order.

There have been few studies of prosecutorial misconduct. The cases are hard to identify, because they are simply not tracked in court databases. Instead, researchers have to rely on prominent cases memorialized in case law or anecdotal information.

According to a Pulitzer Prize-winning study by Ken Armstrong and Maurice Possley at the Chicago Tribune, between 1963 and 1999, at least 381 homicide convictions nationwide were thrown out for those infractions, including 67 in which the defendant had been sentenced to death.

And according to the Tribune, though the appellate courts frequently excoriated the prosecutors' actions, only five were punished, but not by any state lawyer disciplinary agency. More frequently, the Tribune reporters wrote, the offending prosecutors were rewarded for getting the convictions.

A similar study conducted in 2010 by Possley and Santa Clara University law professor Kathleen Ridolfi on behalf of the Northern California Innocence Project identified 707 instances of prosecutorial misconduct between 1997 and 2009 in California courts. But only 159 of those cases resulted in a mistrial or a reversed conviction or sentence. The study found that prosecutors were disciplined in only 1 percent of those cases.

Ridolfi and Possley also took a look at Arizona and found 20 state and federal cases between 2004 and 2008 in which prosecutors were found to have committed misconduct. Only five of the convictions were reversed. No prosecutors were disciplined.

'Harmless error'

In Arizona, all death sentences are subject to a mandatory "direct" appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court. The Arizona Republic reviewed all direct appeals of death sentences issued by the court between 2002 and the present.

Among those 82 direct appeals, there were 42 in which the defendants alleged prosecutorial misbehavior or outright misconduct, 33 of them from Maricopa County, which, as the largest county, has the busiest Superior Court.

The Supreme Court justices found that impropriety or misconduct had occurred in 18* of those 42 cases. But only two were reversed and remanded because of the behavior (in one case characterized only as overreaching). Two prosecutors were disciplined.

The offenses varied in seriousness from rolling eyes and sarcasm to introducing false testimony and failing to disclose evidence that might have helped the defendant.

But, overwhelmingly, even when misconduct was found, the high court determined that it was "harmless error," the defendant would have been convicted anyway, or the judge had cured the problem by making a jury instruction. Some of the most egregious instances do not show up in The Republic's study because the misconduct triggered a mistrial or caused the prosecution to offer a sweetheart plea deal; for instance, when a prosecutor had improper contact with a disgruntled member of the defense team or when it appeared as if the state had been listening in on a defendant's jail calls from his attorney.

According to case law, in order to declare a mistrial for prosecutorial misconduct, a trial must be "permeated" with bad behavior on the part of the prosecutor that "so infects the trial with unfairness as to make the resulting conviction a denial of due process."

Judges are reluctant to risk such drastic measures. If a judge or appellate court were to reverse a case because of misconduct, the defense could claim it amounts to double jeopardy, making it impossible to retry the suspect.

Prosecutors are allowed great latitude during closing arguments, the justices wrote over and over in the death- sentence direct appeals. Or because a defense attorney didn't object at the time of the alleged infraction, the defendant forfeited the option of appellate scrutiny.

"There are no consequences," said Susan Corey of the Office of the Legal Advocate, one of the county's three indigent-defense agencies. "There's absolutely no repercussion."

The majority of attorneys disciplined by the state Bar are attorneys who handle money: divorce attorneys, probate attorneys, civil attorneys. More defense attorneys than prosecutors are referred to the Bar, partly because the County Attorney's Office has an ethics committee.

It was established by former Maricopa County Attorney Romley. His successor, Andrew Thomas, focused on attacking defense attorneys. Thomas was later disbarred.

Montgomery said the ethics committee "only looked at possible referrals (to the disciplinary agencies) of judges and defense attorneys."

He said that it now looks at prosecutors as well, though he would not reveal any details or if anyone had been referred.

"Sometimes defense attorneys are hesitant to file Bar complaints against prosecutors because they're afraid for their next case," said John Canby from the Maricopa County Office of the Legal Defender, another of the three county defense agencies. "Playing nice and getting a good plea is usually the way to go."

"Lawyers in general don't like filing Bar charges," said Karen Clark, who represents other attorneys charged with ethical violations and has served as a prosecutor for the Bar.

"Nobody likes a rat," Clark said.

Repercussions possible

Filing a complaint, in fact, can have more repercussions for a defense attorney than unethical conduct has for prosecutors, as Rick Lougee discovered when he referred a prominent Pima County prowsecutor named Ken Peasley to the state Bar.

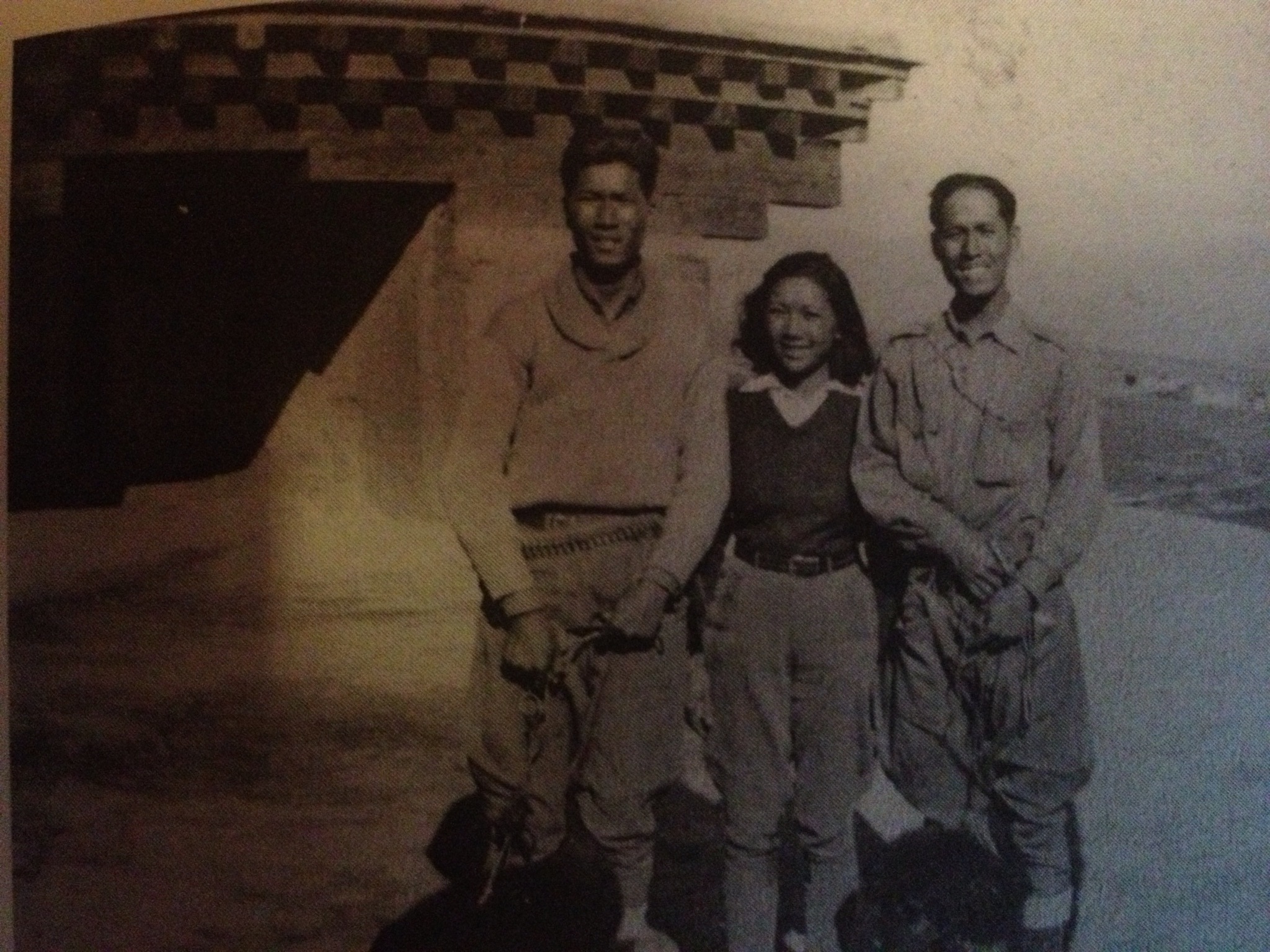

Peasley was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 1994, the year after he got death penalties imposed against two men and a teenager charged with murdering three people in a South Tucson mom-and-pop store called the El Grande Market.

During his career, Peasley prosecuted 140 murder cases, about 60 of them capital cases. He was a death-penalty machine, charming, forceful, well-respected by judges and lawyers alike. Except that he cheated.

"Prosecutors like Peasley have learned that you try people, not facts," Lougee said.

They go after the defense attorneys, the witnesses. They convince the jury that regardless of the facts, the defendant is a bad person and must be guilty of something.

Peasley got all three of the El Grande Market defendants sent to death row, largely on the testimony of an informant. But Peasley misrepresented the informant's knowledge, claiming that police knew nothing of the defendants until the informant brought them up. In fact, police were already aware of them. Nonetheless, Peasley lied to the judge and the jury and encouraged a witness to commit perjury.

Two of the three convicted murderers were granted a new trial because the jury foreman in their joint trial wavered on whether he supported the verdict when the jurors were polled.

The two defendants granted retrials were tried separately the next time. Peasley brought in the same perjured testimony during the retrials. One of the defendants was sent back to death row. Lougee got the other defendant acquitted in 1997, but he had figured out the deception. He filed his Bar charge that Peasley conspired to present false testimony and had repeated the perjury in the retrials.

The complaint made no difference at first, and Peasley was promoted shortly after the complaint was filed. He was named Prosecutor of the Year again in 1996. Judges rallied around him. He traveled the state to train other prosecutors. He won national awards.

Lougee said he was shunned by the legal community for having made the accusation.

But the state Bar took the complaint and passed the investigation to Karen Clark. It took Clark seven years to work out the case, but it ended, in 2004, with Peasley being disbarred by the Arizona Supreme Court. He has since died.

After his disbarment, the death penalty from the retrial was thrown out because of Peasley's behavior. The third defendant remains in prison, though his death sentence was commuted to life in prison when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that killers cannot be executed for murders they committed before the age of 18.

"Ken Peasley corrupted the system for 15 years," Lougee said. "That puts the system at risk for more than just my clients."

*After this series was published, two Deputy Maricopa County Attorneys complained about having cases included in the online database. One was a case in which the Supreme Court wavered over whether a prosecutor had gone over the top but concluded that even if he had, the trial judge had dealt with the problem. The second was a clear-cut Brady violation that compelled a judge to preclude evidence; the prosecutor argued that the Supreme Court had not found the misconduct, even if the trial judge did. The newspaper wrote corrections. Nothing other than the numbers in the database were affected.

PROSECUTORS UNDER SCRUTINY ARE SELDOM DISCIPLINED

Accusations of misconduct rarely result in mistrials

October 28, 2013

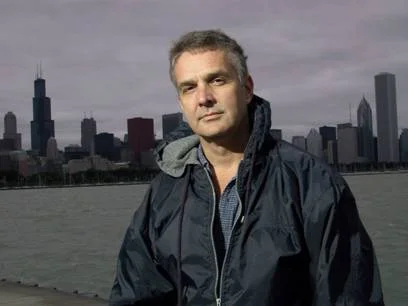

Richard Wintory was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 2007.

Wintory had spent 20 years as an assistant district attorney in Oklahoma, another seven in the Pima County Attorney's Office, and by 2010 had moved on to the Arizona Attorney General's Office, where he continued to try criminal cases, especially death-penalty cases. Now he is chief deputy in the Pinal County Attorney's Office.

He is also the focus of an investigation by the State Bar of Arizona because a Pima County Superior Court judge referred him to the Bar for improper contact with a member of a murder suspect's defense team.

Prosecutors are frequently accused of misconduct during criminal cases, and even if a trial judge or a court of appeals agrees that they acted badly, it rarely affects the conviction or sentence of the trial defendants.

Wintory calls himself an "impassioned" attorney; others might say he pushes the envelope.

"In the 30 years I've been a prosecutor, I've had many people file complaints and lawsuits against me, but I've never been disciplined," he said.

In Arizona, prosecutor misconduct is alleged in half of all capital cases that end in death sentences. Half the time, the Arizona Supreme Court agrees that misconduct occurred in those instances, but it rarely throws out a conviction or sentence because of it.

The Arizona Republic reviewed all of the Arizona Supreme Court opinions on death sentences going back to 2002. Of 82 cases statewide, prosecutorial misconduct was alleged on appeal by defense attorneys in 42 and the court found improprieties or outright misconduct in 18* instances. But only two of those death sentences were reversed because of the improprieties, and only two prosecutors were disciplined.

The offenses varied in seriousness from excessive sarcasm and vouching for the sincerity of witnesses to introducing false testimony and failing to disclose evidence that might have helped the defendant. But overwhelmingly, even when misconduct was found, the high court determined that it was "harmless error." The most serious examples did not appear in those cases because the misconduct caused a mistrial or the prosecution offered a favorable plea agreement to avoid mistrial, as in Wintory's case.

It is rare for prosecutors to be referred to the state Bar for misconduct, let alone be disciplined by the Bar or sanctioned by trial judges. And whether Wintory will be disciplined remains to be seen.

Formal complaint

Wintory had a history of allegations of prosecutorial misconduct in death-penalty cases before he came to Arizona. One death-penalty sentence he obtained in Oklahoma was thrown out because of Wintory's closing argument, which included "yelling and pointing at the defendant as he addressed him directly," according to a ruling by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals.

"This Court finds that the prosecutor in this case committed serious and potentially prejudicial misconduct," the opinion went on to say.

Wintory says he learned from the experience.

"Since that trial, I don't point at defendants. I don't do closings like that anymore," he said. "The reason why is you don't want to put (the victim's) family through those kinds of cases."

In 2010, while at the Pima County Attorney's Office, Wintory got an indictment against Darren Goldin, who was accused of hiring a hit man to kill a fellow drug dealer named Kevin Estep in March 2000. Goldin, the triggerman and a third accomplice had already been convicted of another drug-deal hit in Maricopa County. Goldin was sentenced to 16 years in prison on his conviction of second-degree murder

Wintory changed jobs before the case went to trial, but he took it with him to the Arizona Attorney General's Office, where he worked out of the Tucson office. He sought the death penalty in the Pima County case.

Capital cases require that defense attorneys find mitigating evidence that may persuade a jury to spare the defendant's life. Goldin was adopted, so his defense team hired a "confidential intermediary" to track down Goldin's birth mother. She found the mother and got her to tentatively agree to cooperate in Goldin's case.

But then the intermediary got into a disagreement with the defense attorneys over their decision not to tell the birth mother that Goldin was in prison, according to the state Bar investigative file. The intermediary withdrew from the case, and shortly after, the birth mother decided that she did not want to cooperate after all. Then the intermediary called Wintory and left a message.

It is highly improper for prosecutors to have secret contact with members of the defense team. But Wintory called her back, at least eight times, according to the record, even after the judge in the case had told him to cease contact with her.

Wintory's supervisors questioned the number of calls between Wintory and the defense-team member, but Wintory was said to be evasive. He claimed he had not learned anything about defense strategy, but he did know that the birth mother had also been adopted and knew nothing about her own family history that could help in the case.

In May 2012, Wintory's superiors at the Attorney General's Office took him off the case. That August, the office withdrew its intent to seek the death penalty. With the case in a tailspin, Goldin was offered a plea agreement to second-degree murder and a prison sentence of 11 years, five years less than the presumptive sentence for that crime.

The Bar investigative file says the death notice was dropped primarily because of case law from another Arizona county, but that the "apparent misconduct" figured into the decision to offer a reduced sentence.

"Whatever I did or didn't do had no influence on the plea," Wintory told The Republic.

When Pima County Superior Court Judge Paul Tang accepted the plea, he noted the "apparent misconduct allegedly engaged in by the prosecutor." At Goldin's sentencing, Tang told the defendant how lucky he was to have reaped the benefit of Wintory's conduct; then Tang noted that he would report Wintory to the Arizona State Bar.

Earlier this month, the Bar filed its formal complaint against Wintory, charging him with violating three ethical rules: knowingly making a false statement of fact or law or failing to correct a false statement; engaging in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation; and engaging in conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice.

A Bar spokesman said a disciplinary hearing will be scheduled, unless Wintory reaches a settlement.

"I'm confident that if we get before a hearing panel and lay the facts out, they will see I had no intention to mislead anyone on this matter," Wintory said.

Slow-moving process

The disciplinary process is not rapid. It took seven years to disbar Ken Peasley, a Pima County prosecutor who was caught presenting testimony he knew to be false. Disbarment, however, is extreme, and Wintory could be punished with lesser sanctions, such as a suspension.

In 2004, Peasley was the first American prosecutor to be disbarred because of his conduct in a death-penalty case, according to the New Yorker magazine.

Arizona has had two more prosecutors disbarred for ethical violations since then. Former Maricopa County Attorney Andrew Thomas and one of his deputies, Lisa Aubuchon, were disbarred in April 2012 for filing criminal charges and a civil racketeering lawsuit against Superior Court judges and Maricopa County officials to further Thomas' political goals. Two other deputies received lesser sanctions for their participation in the affair.

"The only people that got anything out of his 'reign of error' were judges and supervisors," defense attorney Susan Corey said. Several of Thomas and Aubuchon's targets received vindication, and tidy court settlements.

Thomas and Aubuchon were not charged criminally for their actions, prosecutors are prosecuted even less frequently than they are disbarred, but it took three years for the system to rein them in and cost the county more than $5 million to settle lawsuits from judges and officials and millions more in legal fees.

"It's a culture that's set from the top," said Karen Clark, an ethics expert who prosecuted Peasley. "If you have a bad-apple prosecutor at the bottom, it's not tolerated. But when it comes from the top, it's rewarded."

During Peasley's tenure, there were two other Pima County prosecutors who came under scrutiny by the state Bar; one of them was suspended.

Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery says he has beefed up prosecutor training to avoid misconduct and maintains an ethics committee to look into the actions of prosecutors, judges and defense attorneys alike.

"I'm trying to create an environment where prosecutors hold each other accountable," he said.

But Montgomery admitted he was not aware of many of the instances of misconduct or improprieties that are described over the course of this series, even those that occurred while he has been in office. That information rests with the middle-management supervisors, he said.

Montgomery has spent much time this year on statewide issues, lobbying against the medical-marijuana law passed by voters, for instance, and defending an Arizona abortion law found unconstitutional by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

He said he does not weigh in on how prosecutors try their cases. "The attorneys are trying the case, I'm not going to step in," he said. "They're on their own."

And if they need to be put in their place, "that's the job of the judge. It's the job of the defense attorney to object," he said.

Minor sanctions

Even when prosecutors do get called before the Bar, most sanctions are minor.

Thomas Zawada, a contemporary of Peasley and a fellow prosecutorial superstar in the Pima County Attorney's Office, was disciplined in 2004 for misconduct during a murder trial 10 years earlier. According to an Arizona Supreme Court opinion, the state Bar inquiry into his conduct found that Zawada's “misconduct included (a) appeals to fear by the jury if (the defendant) was not convicted, (b) disrespect for and prejudice against mental health experts that led to harassment and insults during cross-examination, and (c) improper argument to the jury."

The Supreme Court justices thought that Zawada's behavior was so egregious that it threw out the murder conviction and attached double jeopardy so that the murder suspect could not be retried. As punishment, the state Bar hearing officer recommended that Zawada be censured, put on probation for six months and told to seek continuing education in dealing with psychological testimony. Instead, the high court suspended Zawada from practicing law for six months and one day, meaning that he would have to reapply to the Bar afterward. According to the state Bar website, Zawada has never been reinstated.

Deputy Maricopa County Attorney Ted Duffy was suspended from practicing law for 30 days in 2009 after being referred to the Bar by a Superior Court judge for repeatedly disobeying a judge's orders in a capital murder case to not mention evidence that had been precluded from trial, including the defendant's prior convictions. The trial ended in a hung jury, and the defendant was acquitted when Duffy took him back to trial.

But most findings of misconduct are not reported to the state Bar and have little or no consequence for the prosecutor involved.

Even when they make findings of prosecutorial misconduct, judges do not necessarily report the offenders to the Bar, which would then investigate the offenses in light of the state's rules of attorney ethics and determine whether to set to disciplinary hearings.

Jonathan Mena Cobian, who goes by the name Alex, was at his mother's house in Phoenix when a group of gang members came looking for his half-brother John Mitchell Mena to take him to task for trying to leave their gang. According to court filings, they asked Alex to step outside to help them with a car problem, then attacked him, and when Alex knocked one to the ground, they told him that they would come back to kill him.

Another brother had called 911; Alex talked to the dispatcher about the attack and the police officer who came to the house advised Alex that he would be within his rights to carry a firearm in case the gang members returned. Alex went to get his guns, picked up John at the mall and returned to their mother's house.

According to motions filed by Alex's defense attorneys, the gang members pulled into the driveway behind him. Alex told them to leave, and when they advanced on him and John, the brothers fatally shot two of them. Someone inside the home called 911 again.

Alex and John were charged with first-degree murder. Court records show that the prosecutor, Deputy County Attorney Eric Basta, did not want to turn over evidence of the victims' criminal past, a matter brought to the Arizona Court of Appeals. The case was remanded to the grand jury twice, and Superior Court Judge George Foster ordered Basta to play the potentially exculpatory 911 tapes for the grand jury. Basta had already been told to do so by another judge who had the case before Foster.

When Basta refused, Foster threw out the indictment. He wrote in his ruling that Basta had denied due process to the two defendants. "The court further finds prosecutorial misconduct and that the appropriate remedy is dismissal without prejudice of the indictment as to both defendants," Foster wrote. Then he sealed the order from the public record.

When asked why he didn't refer Basta to the Bar, Foster told The Republic that he felt that dismissing the indictment was sanction enough.

Alex and John were subsequently reindicted on second-degree murder and aggravated assault charges, respectively, and their case is expected to go to trial this fall. misconduct

Bill Montgomery said he was not aware of the case or of the finding of misconduct. Basta declined a request for an interview.

A STAR PROSECUTOR’S TRIAL CONDUCT CHALLENGED

Justices critical of Arias prosecutor's behavior in other cases

October 29, 2013

Juan Martinez was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 1999, more than a decade before he became a media darling with his performance in the Jodi Arias murder trial.

This year, Martinez persuaded a jury to find Arias guilty of first-degree murder, but the jurors could not reach consensus on whether to sentence her to death or life, and Arias likely faces a new trial to make that decision.

Martinez helped send seven other killers to death row since he was hired by the Maricopa County Attorney's Office in 1988.

He was accused by defense attorneys of prosecutorial misconduct in all but one of those cases. The Arizona Supreme Court characterized his actions as constituting misconduct in one of them and cited numerous instances of "improper" behavior in another, but neither rose to the level where the justices felt they needed to overturn the cases. Allegations of misconduct by Martinez in the second case and at least two others are pending in state and federal courts.

It is not uncommon for defense attorneys to allege misconduct against prosecutors. A study by The Arizona Republic determined that it has been alleged in about half of all death-penalty cases since 2002 and validated in nearly one-quarter of them.

But it is rare for Supreme Court justices to call out a prosecutor’s conduct in open court.

One day in mid-2010, the Arizona Supreme Court was on the bench as lawyers presented arguments during the direct appeal of a first-degree murder conviction and death sentence for a man named Mike Gallardo, who killed a teenager during a Phoenix burglary in 2005.

Transcripts show that Justice Andrew Hurwitz turned to the attorney representing the Arizona Attorney General's Office, the prosecutorial agency that handles death-penalty appeals.

"Can I ask you a question about something that nobody's discussed so far?" he asked. "The conduct of the trial prosecutor. It seems to me that at least on several occasions, and by and large the objections were sustained, that the trial prosecutor either ignored rulings by the trial judge or asked questions that the trial judges once ruled improper and then rephrased the question in another improper way. ... Short of reversing a conviction, how is it that we can ... stop inappropriate conduct?"

The assistant attorney general struggled to answer.

Justice Michael Ryan then stepped into the discussion.

"Well, this prosecutor I recollect from several cases," Ryan said. "This same prosecutor has been accused of fairly serious misconduct, but ultimately, we decided it did not rise to the level of requiring a reversal," Ryan said. "There's something about this prosecutor, Mr. Martinez."

There had been multiple allegations of prosecutorial misconduct against Martinez in Gallardo's appeal. Ultimately, in its written opinion, the court determined that Martinez had repeatedly made improper statements about the defendant. During the oral argument before the Supreme Court, the justices fixed on a question that Martinez asked three times, even though the trial judge in the case had sustained a defense attorney's objections to the question.

But, in the end, the justices ruled that Martinez's behavior still did not "suggest pervasive prosecutorial misconduct that deprived (the defendant) of a fair trial."

And, as the justices noted, it was not the first time that Martinez had walked away unscathed.

"It's his MO," Deputy Maricopa County Public Defender Tennie Martin said when asked about trying cases against Martinez. "He's kind of Teflon."

Retired county Superior Court Judge Kenneth Fields, himself a former federal prosecutor, said, "You're at war, almost nuclear war, the minute you come up against him."

Fields was one of several judges who sued Maricopa County and received settlements after being falsely targeted by the anti-corruption crusade of disbarred former County Attorney Andrew Thomas and Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

Martinez declined to talk to The Republic for this story. The County Attorney's Office refused to turn over his personnel file despite a request made by The Republic under the state's public-records law. The office said the denial was "due to the best interests of justice."

The National District Attorneys Association honored Martinez with its "Home Run Hitter Award for Outstanding Prosecution" for 2013 because of the Arias murder trial and conviction.

The general public loved the trial, but Martinez's live-streamed aggression in the courtroom, his pacing and arm-waving, his constant sarcasm raised concerns among legal pundits. Arias' defense attorneys filed numerous motions for mistrial alleging prosecutorial misconduct. All were denied by the judge.

County Attorney Bill Montgomery denounced the circus atmosphere in the courtroom, though he did not criticize his prosecutor.

"I do not believe the coverage of that trial furthered the understanding of the criminal-justice process," Montgomery said. "I had no idea it was going to turn out like that."

More allegations

Not counting the allegations of misconduct during the Arias trial this spring, Martinez has been called out in at least two other cases this year.

The defense attorney in the Richard Chrisman trial, which ended in a hung jury on two counts last month, filed motions in January to protest Martinez's failure to disclose an expert witness whom Martinez had retained a year and a half earlier. The judge ordered that the defense attorney be allowed to interview the tentative witness.

Then, during the penalty stage of the trial, the defense attorney asked for a mistrial on the grounds of misconduct because he thought Martinez was trying to shift the burden of proof from the state to the defendant. The judge called it "close to the line of burden shifting" but let the trial go on.

Earlier this year, another attorney referred Martinez to the State Bar of Arizona after a dispute over whether he and the defense attorney had reached an agreement on preliminary court actions and for failing to file a pretrial statement.

According to state Bar investigative files, Martinez denied there had been an agreement but acknowledged he "unknowingly failed to comply" with the deadline for the pretrial statement. The Bar closed the case in June; it did not sanction Martinez, but sent him an "instructional comment" on filing documents "in a timely manner."

Misconduct has to be "pervasive" for a judge to throw out a case or for the Supreme Court to throw out a conviction. It is rare for a prosecutor to be sanctioned by the court or disciplined on ethical grounds by the state Bar.

A study by The Arizona Republic found that improper behavior by prosecutors was alleged in half of all death penalties reviewed by the Arizona Supreme Court since 2002. The high court found that prosecutorial impropriety or outright misconduct had indeed occurred in nearly half of those allegations, but only twice found that it rose to a level where the conviction was overturned.

But other instances of misconduct do not appear among those numbers because the misconduct caused a mistrial or encouraged prosecutors to offer a plea deal to a lesser sentence to avoid mistrial.

Former Deputy Maricopa County Attorney Noel Levy, who was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 1990, was never sanctioned, even though he helped put Debra Milke on death row that year based on a questionable confession. He and law enforcement were successful in blocking the defense attorney's attempt to impeach the detective who said Milke confessed.

And then two years later, Levy helped put an innocent man on death row, as well. Ray Krone spent 10 years in prison before he was exonerated by DNA. Milke's conviction and death sentence were overturned in March of this year. Courts acknowledged prosecutorial lapses in both cases and overturned the verdicts and sentences.

Montgomery also refused to divulge Levy's personnel file "due to the best interests of justice."

Levy told The Republic: "I just did my job, and I did it ethically. I'm fully aware of my ethical obligation to present evidence. It's up to the jury to make a decision."

Tactics challenged

Sex and outrage often figure prominently in Martinez's cases.

In 2004, Martinez persuaded a jury to send Wendi Andriano to death row for murdering her husband in an especially cruel manner. She poisoned him, and when that didn't work fast enough, she stabbed and beat him to death.

Like Arias, Andriano claimed to be a victim of domestic abuse. On appeal, Andriano's defense team argued that Martinez had unfairly prejudiced the jury because "he took every opportunity to infuse the trial with marginally relevant information about Andriano's partying and man-chasing."

The Arizona Supreme Court pushed away the allegation, saying that closing arguments are not evidence and that the jury would have known that because it had been so instructed.

During a second-degree- murder trial in 2005, Martinez accused the defendant of covering up prior crimes that the judge had ordered withheld from the jury. Martinez revealed them anyway, which the Arizona Court of Appeals deemed improper. Then, during his rebuttal, Martinez repeatedly compared the defense attorney, who is Jewish, to Adolf Hitler and his "big lie."

The trial judge told the jury to disregard the remarks but did not grant a defense request for a mistrial. The Appeals Court called the analogy "reprehensible" but did not overturn the case because, "In recognition of the frequently emotional nature and sometimes rough and tumble quality of closing argument, attorneys, including prosecutors, are allowed wide latitude in their arguments to the jury."

Also in 2005, Martinez obtained convictions and death sentences against Cory Morris, who killed five prostitutes in 2002 and 2003 and dumped their decomposing bodies in alleys. Martinez told the jury that Morris took them to the camper bus he parked behind his aunt's house in the Garfield neighborhood of central Phoenix, strangled them during sex, and then continued to have sex with their bodies until they rotted and fell apart.

On appeal, Morris' lawyers noted that Martinez and not the medical examiner had decided that Morris engaged in necrophilia. Once again, the Supreme Court justices wrote that prosecutors have "wide latitude."

"While the evidence in this case does not compel the conclusion that Morris engaged in intercourse with the corpses of the victims, the record includes sufficient evidence to permit the prosecutor to make such an argument," the justices wrote when affirming Morris' death sentences. Furthermore, they pointed out, Morris' trial attorney had not objected to the allegations during trial.

The high court did disapprove of Martinez singling out jurors in comments during his arguments, drawing comparisons to Morris and his victims, which it deemed misconduct.

It found Martinez to have been inappropriate when at one point he took a jacket worn by one of the dead out of a plastic evidence bag for the jury's "smelling pleasure." The jacket filled the jury area with the smell of decomposition, but the justices said: "This single remark did not deprive Morris of a fair trial."

Morris' convictions and death sentences were upheld, but the allegations of necrophilia are being debated in Morris' ongoing appeals. In its filings, the state reiterates the words of the Supreme Court that Martinez had "wide latitude" to deduce necrophilia from the facts at hand; the appeals judge felt there was room for argument and set an evidentiary hearing.

'Everything ... is attack'

In 2009, Martinez tried Douglas Grant, who had been charged with first-degree murder in the drowning of his wife, Faylene. It was another bizarre case.

Grant, a dietitian who worked with the Phoenix Suns, had divorced Faylene and was dating at least two other women. Faylene, who was a self-described Mormon mystic, asked Grant to repent and remarry her because she had visions that she would soon die and she needed to have a husband to be admitted into heaven.

She also selected one of Grant's interim girlfriends as a suitable mother to raise their children after her death, and she encouraged Grant to marry the woman when she was gone. Faylene wrote numerous letters to friends and relatives about her anticipated demise and filled her journals with her thoughts.

On Sept. 24, 2001, while on a second honeymoon with Grant to a sacred Mormon site in Utah, Faylene fell from a cliff. Her visions told her that would be the day she died, but instead, she survived with injuries that were painful but not life-threatening. A relative sent to Grant's house shortly afterward found many of Faylene's prized possessions laid out and tagged with Post-it notes telling who she wanted to have them after her death. Two days later, Faylene drowned in a bathtub while impaired by pain medication and sleeping pills. At first, the death was ruled an accident; then, four years later, Grant was arrested and charged with murder.

Grant was represented by Mel McDonald, a former Superior Court judge and a former U.S. attorney for the District of Arizona.

The prosecutorial high jinks, which McDonald chronicled in motions, began in the pretrial stage. Martinez had to be compelled to turn over Faylene's letters and journals in which she happily proclaimed that she would soon die and go to heaven.

The court record shows that Martinez avowed that he had turned over all farewell letters from Faylene when he hadn't. Martinez also denied having tape recordings of interviews with certain witnesses, though they eventually materialized. The judge ordered that the materials be turned over and threatened to dismiss the case "on the basis of ongoing discovery issues."

In pretrial hearings, Martinez grilled Grant's new wife and another former girlfriend about intimate details of their sex lives, down to whether they wore thong underwear or had performed oral sex in cars.

During his opening statements in the 2008-09 trial, Martinez claimed that Grant had lifted Faylene while she was unconscious and had placed her in the bathtub to drown her. In his closing arguments, he said Grant had her kneeling at the side of the tub and pushed her head underwater. He feigned surprise when a witness on the stand came up with a story of which McDonald had not been informed.

The courtroom interaction was vicious.

"Everything he does is attack," McDonald said. "There's a time to attack, but you don't attack every witness on every point, every time. I couldn't even ask a question without him objecting."

Grant was portrayed throughout the trial as a sex-obsessed Lothario, and the jury told the media afterward that they had convicted him because he was a "scuzzbag."

Martinez did not get a first-degree-murder conviction, however. The jury found Grant guilty of manslaughter, and the judge sentenced him to only five years in prison. McDonald said he did not file appeals alleging misconduct to avoid the risk that Grant might be awarded a new trial and then be found guilty of a more serious murder charge.

"If you go in on a Murder 1 and walk out with only five years in prison, you would have to be brain dead to file an appeal," he said.

Contentious Arias trial

The Jodi Arias trial won Martinez international attention, but, like other trials, it has been rife with allegations of misconduct.

Arias' attorneys filed numerous motions to protest Martinez's actions, not just in trial but in the years of discovery and evidentiary hearings between the 2008 murder and the 2013 trial.

The two judges who handled the case over those four years repeatedly ordered Martinez to produce e-mails, photographs and social-media posts that fueled the salacious case.

Martinez would repeatedly deny such materials existed. A month before the jury was picked, he was still fighting with defense attorneys over the whereabouts and contents of victim Travis Alexander's computer.

When Arias' defense attorneys asked for more time to study the thousands of images in its drives, Martinez objected, saying that the defense had already had four years in which to analyze the computer.

Arias admitted that she killed Alexander and claimed that she shot him after he attacked her. For four years, police and prosecution maintained that Arias first shot Alexander and then stabbed him and slit his throat. But days before jury selection, Martinez changed the facts of the case, saying that Arias had shot Alexander last instead of first. Arias' attorneys, Kirk Nurmi and Jennifer Willmott, protested that the rationale for seeking the death penalty had been based on the first theory.

They filed a motion for mistrial alleging prosecutorial misconduct when Martinez appeared on television, signing autographs and posing for photos with fans.

Martinez verbally attacked Arias and her witnesses. He painted Arias as a sexual predator. He asked compound questions and then accused witnesses of being non-responsive when they would not answer yes or no.

"I would not have let the cross-examinations go on for that long," said Fields, the retired judge. "It was just badgering and bullying the witnesses in an attempt to ruin their credibility. It crossed the line."

As video and transcripts later showed, many of the trial's most contentious moments took place in the judge's chambers or at the bench, out of earshot of the rest of the courtroom and the cameras. Etiquette is a given during court proceedings. Martinez was frequently insulting.

The first question he posed to Arias during cross-examination set the tone, when he displayed a photograph to the courtroom and described it to her as a "picture of you and your dumb sister."

One day at the bench, as the attorneys debated whether to admit a statement about whether Alexander wanted to kill himself, transcripts show Martinez said, "But the thing is that if Ms. Willmott and I were married, I certainly would say, 'I f---ing want to kill myself.'"

Willmott objected, and two days later at another bench conference, Martinez said to Willmott, "Well, then, maybe you ought to go back to law school."

Nurmi asked Judge Sherry Stephens to step in, but she did not.

"In my view, that would have been a fine," Fields said. "I probably would have reported him to the Bar. It shows his bias. It's just inappropriate."

But it didn't matter. Martinez became a rock star. He got the conviction. Whether he ultimately gets a death sentence for Arias remains to be seen.

"All the young prosecutors want to be like Juan Martinez now," said Alan Tavassoli, an attorney with the Maricopa County Public Defender's Office. "He's a role model. And so was Noel Levy."

CAN THE SYSTEM CURB PROSECUTORIAL ABUSES?

Clearer definition of misconduct, strong judicial oversight are key

October 30, 2013

For three days, The Arizona Republic has examined prosecutor conduct and misconduct, citing cases in which prosecutors stepped over the line without suffering consequences to themselves or the convictions they win.

The question remains: What can be done about it?

Options already are in place.

When a prosecutor steps over the line, it's up to the defense attorney to call it to the court's attention, and it's up to the judge to decide whether an offense has been committed and whether it affects the defendant's right to a fair trial.

Yet neither likes to do so.

Prosecutors are arguably the most powerful people in the courtroom: They file the charges and offer the plea agreements. They determine whether to seek the death penalty, and, given mandatory sentencing, predetermine the consequence of a guilty verdict.

Defense attorneys worry that if they cross a prosecutor, future clients could be treated more harshly the next time they face that prosecutor in court. Judges worry about prosecutors who use court rules to bypass those judges who rein them in. Both know that prosecutors are rarely sanctioned by the court or investigated by the State Bar of Arizona for ethical misconduct.

So, overly aggressive prosecutors continue to have their way in the courtroom, as long as they win cases, experts say.

"It comes from this 'end-justifies-the-means mentality,'" said Jon Sands, federal public defender for Arizona. "We'll do anything we can to bring someone to justice."

What is ' misconduct'?

Part of the problem of reining in prosecutorial misconduct is defining it.

When a defense attorney does something wrong while defending a criminal client, it's called "ineffective assistance of counsel."

When a judge does something wrong, it's called "judicial error."

But when it's the prosecutor who is under scrutiny, it's called "prosecutorial misconduct." It's a fuzzy concept rooted more in constitutional law than in rules of professional conduct: A "term of art," according to the American Bar Association.

But what constitutes misconduct depends on a judge's ruling. Even then, such rulings tend to blur the distinction among what is improper, "inartfully stated," bad judgment or outright.

"The vast, vast majority of prosecutorial-misconduct claims go to inadvertent slip-ups rather than calculated interference with the wheels of justice," said Judge Peter Swann of the Arizona Court of Appeals.

It's a view shared by defense attorneys and prosecutors, as well. In 2009, the American Bar Association recommended that states amend their rules of court procedure to create a new term of “prosecutor error" to force judges to determine the intent of the prosecutor.

"Prosecutors are human and will make mistakes," said Yavapai County Attorney Sheila Polk, who is president of the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys Advisory Committee. "The judge needs to address it at the time, especially for a less experienced attorney.

"However, if an experienced attorney is playing with the rules and the judge knows it is deliberate (or has seen it before), then the court needs to address it. ... It simply cannot go unaddressed. That goes for defense attorneys as well as prosecutors."

Judges make a difference

When an allegation of misconduct is made before or during a trial, judges have to think long and hard about whether to dismiss a case or sanction a prosecutor.

That is the question facing Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Sally Duncan in the case of Jeffrey Martinson.

Martinson was found guilty of murdering his 5-year-old son. But in March 2012, before the jury could decide whether to impose the death penalty, his attorneys, Treasure VanDreumel and Mike Terribile, uncovered juror misconduct, and Duncan declared a mistrial.

Deputy County Attorney Frankie Grimsman then filed multiple motions to have the judge and the defense team removed from the case, all of which were denied by Duncan and by the court's then-presiding criminal judge, Douglas Rayes.

Grimsman also tried to dismiss the original indictment and re-indict Martinson, this time without a notice to seek the death penalty, which intentionally or coincidentally, would result in a new judge and defense team. In the original indictment, Martinson had been charged with felony murder, meaning the child died during the commission of another crime, namely child abuse. Grimsman was now alleging premeditated murder.

Duncan refused to dismiss the original indictment and pointed out in a ruling that through the first trial, Grimsman had said that she did not have evidence to charge Martinson with premeditation but had argued it anyway.

"The court further finds that the state either deliberately disregarded the court's rulings or acted in a willfully blind manner," Duncan ruled in October 2012.

Grimsman appealed Duncan's ruling in the Martinson case to the Arizona Court of Appeals for her right to dismiss the original indictment and won, sort of. The Court of Appeals reversed Duncan's ruling but gave Duncan the option to determine whether the state attempted to dismiss the indictment improperly.

"The State has done nothing improper in seeking to re-indict this case," Grimsman and another deputy county attorney wrote in a response to Terribile and VanDreumel's motion to dismiss the charges, alleging bad faith. "Defendant has made numerous spurious assertions which have no basis in fact or reality."

Terribile and VanDreumel then filed a motion to dismiss the case altogether, alleging prosecutorial misconduct for charging Martinson with felony murder and then trying him for premeditated murder. They argued the motion case to Duncan on Oct. 3.

Duncan took the case under advisement and, as of this writing, still has not ruled.

The County Attorney's Office declined to comment on the case because it is ongoing.

What can be done?

Karen Clark, a private attorney, not only defends lawyers against state Bar complaints, she prosecutes for alleged ethical lapses that could lead to disbarment. Clark, for example, prosecuted Deputy Pima County Attorney Ken Peasley, who was disbarred in 2004 for encouraging perjury during capital-murder trials.

She says systems are in place to control courtroom conduct without putting bad guys back on the street.

"We are a self-regulating profession. ... Just because the other (checks and balances) aren't working doesn't mean you have to overturn convictions," Clark said. "You get the other wheels working."

Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery said that he is "trying to create an environment where prosecutors hold each other accountable."

Montgomery told The Republic that his office's ethics committee, which historically has filed complaints against defense attorneys and judges, now also considers prosecutor ethics.

But Montgomery's office has not responded to a request for details about the committee made July 30 under the state's public-records laws.

The request asked for the names of the people on the ethics committee and a list of judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys referred to the office ethics committee and a list of those whom the ethics committee referred to the state Bar.

Polk said there is communication in Yavapai County among judges, prosecutors and public defenders to identify bad actors before they cause damage.

But for a defense attorney to make a referral puts him or her in the crosshairs, according to David Euchner, president of Arizona Attorneys for Criminal Justice and an assistant public defender in Pima County.

"They're afraid of the blowback they'll get," Euchner said.

To combat the threat of reprisal, his organization of defense attorneys has recently created a panel to gather information and file Bar complaints against rogue prosecutors. It is intended to mirror the ethics committee of the Maricopa County Attorney's Office.

"That's why we decided to put together our own panel to give attorneys a cover," Euchner said. "So that a statewide association files the complaint, not the individual attorney."

Judges worry about "blowback," as well.

"Once the prosecutors gained the ability to use charging decisions to shape sentences (due to mandatory sentencing), it was a huge power shift," said Swann, the Appeals Court judge. "The Legislature empowers the prosecutors and defangs the judges."

Of the approximately 40,000 felony cases filed each year in Maricopa County, most end in plea agreements. Only 2 percent go to trial, and most of those result in guilty verdicts. So, by filing charges or offering plea agreements, the prosecutor is, in effect, also deciding the punishment.

Swann also took issue with prosecutors' ability to make a "peremptory strike" against a judge they don't want to appear before because of that judge's courtroom practices. They are allowed one such strike without having to say why, and they use it to try to gain a tactical advantage in a case. If they want to strike a second judge, they must show cause.

"When judges who take steps to manage their courtrooms are subject to peremptory strikes, it diminishes their control over the courtroom. And it can serve to chill the bench," Swann said.

Defense, prosecution and judges all agree that the final word on defining and curbing prosecutorial misconduct rests with judges.

"The bottom line, judges must report conduct," Polk said. "To sit from afar and paint a broad brush against prosecutors does absolutely nothing to help us all achieve our high standards of justice and due process."

Swann agreed.

"When a judge thinks a lawyer's conduct is questionable, the lawyer should be referred," he said.

Ariz. prosecutors must now reveal evidence of convicts' innocence

November 15, 2013

If Arizona prosecutors find evidence that shows a convicted person may actually be innocent, they must turn it over to the convict's defense attorneys, according to a new rule for lawyers enacted Thursday by the Arizona Supreme Court.

And if the prosecutors find "clear and convincing evidence" that a defendant is not guilty, according to the amended rule, they must take steps to have the conviction reversed.

The rule was approved over the objection of state prosecutors, who say it is unnecessary.

Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery, one of the prosecutors who opposed the change, declined to comment for The Arizona Republic. The objection to the proposal filed under his name last month said that "we have no real-world examples of prosecutors discovering evidence of the nature that would trigger a duty under this rule."

"Prosecutors in Arizona already fully embrace their roles as ministers of justice when (it) comes to righting wrongful convictions," the filing said.

The objection cited the fact that Montgomery's office recently filed motions to drop charges against people who pleaded guilty to "huffing," that is, intentionally inhaling toxic vapors to get high, when it was discovered that the office had misinterpreted the law.

However, at least one case contests the notion that prosecutors always turn over such exculpatory evidence.

In 1999, a man named Henry Hall was sent to death row for the murder of Ted Lindberry, based largely on the testimony of a jailhouse informant who claimed that Hall had described to him how he had smashed Lindberry's skull and dumped his body in the desert east of Phoenix. The body had not yet been found when Hall was sentenced to death.

But by the time Hall's conviction and sentence were overturned by the Arizona Supreme Court because of juror misconduct in 2001, Lindberry's skeletal remains had been located in the desert west of Phoenix. His skull was not caved in.

The remains were released to Lindberry's family and cremated. Hall's defense attorneys did not learn about the new exculpatory evidence until approximately a year after the remains had been destroyed, according to court documents.

The informant had since died. But Maricopa County prosecutors wanted to use the informant's testimony in Hall's retrial.

Superior Court Judge Roland Steinle refused to allow the testimony because it was proved to be false and because the informant could not be challenged because he was dead. And as a sanction for not disclosing the discovery of the skeletal remains, Steinle agreed to allow the defense attorneys to inform the jury of the lapse.

The prosecutors took the case to the Arizona Court of Appeals, still planning to use the false informant testimony.

In 2011, the appellate court denied the appeal (as well as a request by the defense to throw out the case for prosecutorial misconduct). Prosecutors allowed Hall to plead to second-degree murder and a prison sentence of 16 years; he had already served more than 13.

Montgomery also declined to comment on the Hall case.

If the new amendment, known as Rule 3.8, had been in effect at the time of Hall's conviction, it would have made the prosecutor's duty obvious, though it would not have guaranteed that Hall's first-degree conviction would have been overturned.

The amended Rule 3.8 to the Arizona Rules of Professional Conduct is modeled on rules suggested by the American Bar Association in 2008.

The text of the amendment says, "When a prosecutor knows of new, credible, and material evidence creating a reasonable likelihood that a convicted defendant did not commit an offense of which the defendant was convicted, the prosecutor shall:

"(1) promptly disclose that evidence to the court in which the defendant was convicted and to the corresponding prosecutorial authority, and to defendant's counsel. ...

"(2) if the judgment of conviction was entered by a court in which the prosecutor exercises prosecutorial authority, make reasonable efforts to inquire into the matter or to refer the matter to the appropriate law enforcement or prosecutorial agency for its investigation into the matter."

The amendment goes on to say that when a prosecutor learns that a defendant is not guilty, "the prosecutor shall take appropriate steps, including giving notice to the victim, to set aside the conviction."

Defense attorney Larry Hammond, one of the petitioners who proposed the amendment in 2011, called it "an important step forward to make as sure as we can that there are no people who are not guilty who remain in our prison."

But the state's prosecutors tried to dissuade the Supreme Court from making the amendment.

Pima County Attorney Barbara LaWall wrote in her comments filed with the Supreme Court that she could not order law enforcement to conduct investigations into new evidence and worried that the rule would force prosecutors to investigate the numerous claims of innocence by the state's prison populations.

LaWall did not respond to a request for comment.

The comments by Montgomery's office, filed by Chief Deputy County Attorney Mark Faull, called the investigations "unfunded mandates" and said, "The rule will subject honest, hard-working prosecutors to unnecessary Bar complaints where the burden will be on the prosecutor to prove that his or her action or inaction was 'in good faith.'"

Yavapai County Attorney Sheila Polk, representing the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys' Advisory Council, called the changes "unnecessary, confusing, impractical, and a solution in search of a problem" in her filings with the high court.

She wrote that prosecutors could not be ordered to do investigations and noted that some counties do not have a public defender's office to contact, as required in the amendment.

Polk also did not respond to a request for comment.

The Supreme Court and Chief Justice Rebecca White Berch disagreed with the prosecutors.

The amendment "highlights the special duty of prosecutors to act as ministers of justice and not as advocates who seek to obtain convictions at all costs," Berch said in an e-mail to The Republic.

She added: "It requires affirmative steps to be taken when it appears that a defendant might have been wrongfully convicted.

"Prosecutors represent all citizens, and therefore they (like judges) are held to higher standard and should help remedy any errors that result from our sometimes imperfect system of justice."

Man held in son's '04 death ordered freed

Judge cites prosecutorial misconduct in dismissing first-degree murder case

November 20, 2013

Whether Jeffrey Martinson killed his 5-year-old son, Josh, in 2004 may never be determined in a court of law because of prosecutor misconduct in trying his case.

On Tuesday, a Maricopa County Superior Court judge dismissed the first-degree murder indictment against Martinson with prejudice, meaning that Martinson cannot be retried for murder because of the theory of double jeopardy.

Judge Sally Duncan ordered that Martinson be released from jail at noon on Nov.26. She described the prosecutors' actions as "a win-by-any-means strategy."

The Maricopa County Attorney's Office has options to appeal.

"We will review the Judge's allegations as well as refer the record of the proceedings to our Ethics Committee and Appellate section for review," County Attorney Bill Montgomery said in an e-mail to The Arizona Republic. "We will also review the conduct of defense counsel and that of the Judge for appropriate action."

Duncan wrote a 28-page ruling detailing the conduct by the prosecution team, led by Deputy Maricopa County Attorney Frankie Grimsman.

"When viewing the totality of circumstances, the Court finds that during trial the Prosecutors engaged in a pattern and practice of misconduct designed to secure a conviction without regard to the likelihood of reversal," Duncan wrote.

Duncan then detailed the misconduct. The prosecutors had charged Martinson with felony murder, specifically saying that Martinson's son, Josh, died because of child abuse, and then tried the case as if he were charged with intentional, premeditated murder. Grimsman had been warned by Duncan several times over the course of the trial not to do so.

After the conviction was thrown out because of improper testimony from a medical examiner and juror misconduct, Duncan wrote, Grimsman tried to re-indict Martinson for premeditated murder. She then repeatedly tried to get Duncan and the defense attorneys, Michael Terribile and Treasure VanDreumel, removed from the case.

"Accordingly, the prosecutors relentlessly sought to remove defense counsel and the assigned judicial officer specifically to avoid the risk of acquittal during any trial," Duncan wrote.

Criminal cases, especially homicides, are rarely overturned because of misconduct, even in appellate courts. A recent investigation by The Republic found that only two of 82 death sentences in Arizona since 2002 had been overturned on appeal because of prosecutors' actions.

Verdicts are even less frequently overturned with prejudice by a trial court judge.

"I am pleased that judges at the trial-court level are giving credence to allegations of prosecutorial misconduct," VanDreumel said. "Often, it's a paper tiger and they prefer the decision to be made at the appellate level."

Martinson, 47, has been in jail for nine years awaiting a final verdict.

On the night the child died in 2004, Martinson was in a custody battle with his ex-wife. Martinson claimed he found the boy floating in the bathtub and could not resuscitate him. Then, Martinson claimed, in his anguish, he tried to kill himself but failed.

An autopsy showed the boy had muscle relaxants in his bloodstream, and the medical examiner ruled Josh died of a drug overdose.

It appeared to be a murder-suicide, but Martinson was not charged with first-degree premeditated murder, but rather with first-degree felony murder, meaning prosecutors wanted to prove that Josh died during child abuse by Martinson.

Terribile and VanDreumel argued that the death was consistent with drowning and that there was DNA on the bottle of muscle-relaxant tablets that could not be identified but could not be eliminated as coming from the boy. The defense maintained the boy may have taken the tablets himself, and Terribile pointed out that the pills resembled candy.

After several years of changing defense attorneys, Martinson went to trial in July 2011.

Martinson was found guilty in November 2011, and the jury determined there were aggravating factors that made him eligible for the death penalty. But before the jury could sentence Martinson, a juror came forward to tell Terribile and VanDreumel about what was going on in the jury room. The forewoman was accused of browbeating other jurors into finding Martinson guilty. The guilty verdict was thrown out in March 2012.

In fall 2012, Grimsman told the judge that the original indictment and the intent to seek the death penalty had been dropped and that she had asked that another judge and defense team be appointed. Terribile and VanDreumel fought the new charge.

In late 2012, the Arizona Court of Appeals ruled that Grimsman could indeed re-indict Martinson, unless Duncan found that Grimsman had done so in bad faith.

On Tuesday, Duncan made that finding, in addition to the finding of prosecutorial misconduct.

Defending the case had cost taxpayers $2.97 million as of last July, nearly twice the amount paid for the defense of Jodi Arias.

Prosecutor agrees to 90-day suspension

Rebuke for murder-case misconduct is rare sanction

February 19, 2014

Deputy Pinal County Attorney Richard Wintory has agreed to a 90-day suspension from practicing law because of his conduct during a capital- murder case in 2011 while he was an assistant Arizona attorney general.

In that case, Wintory had several inappropriate telephone communications with a confidential intermediary hired by defense attorneys, according to a signed consent agreement between Wintory and the State Bar of Arizona that was filed Friday with the presiding disciplinary judge of the Arizona Supreme Court.

Wintory also did not reveal to the court, the defense attorney or his own supervisors the number of conversations he had with the intermediary.

Wintory, who was Arizona Prosecutor of the Year in 2007, is now chief deputy to Pinal County Attorney Lando Voyles.

In the consent agreement, Wintory "conditionally admits" that he violated the state's Rules of Professional Conduct for attorneys, specifically a rule under the heading of "misconduct" that he engaged "in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice."

Prosecutors are rarely disciplined for misconduct. Wintory entered the agreement rather than face a disciplinary hearing.

The consent agreement notes that "had this matter proceeded to hearing rather than being resolved by consent agreement, the State Bar would have contended that (Wintory) knowingly engaged in dishonest conduct. (Wintory) would have contended that, while negligent, he acted in good faith and had no intention to be dishonest or to deceive the court of his colleagues."

The agreement needs to be approved by the judge.

Wintory was a prosecutor for 20 years in Oklahoma and had a history of allegations of prosecutorial misconduct in death-penalty cases there before he moved to the Pima County Attorney's Office.

In 2010, he took a case against Darren Goldin, who was accused of hiring a hit man to kill a rival drug dealer 10 years earlier. Goldin had already been convicted of second-degree murder for a similar killing in Maricopa County.

Wintory was going for the death penalty against Goldin in the Pima County case. Wintory took the case with him when he moved to the Tucson office of the Arizona attorney general.

Goldin was adopted, and in order to find information about Goldin's family history that might mitigate a potential death sentence, his defense attorney hired a confidential intermediary to locate Goldin's mother.

The intermediary had a falling out with the defense attorney and, in August 2011, contacted Wintory to help her get legal representation so that she could sue the defense attorney.

Wintory spoke to the intermediary several times over the next few weeks, and in an Aug.22, 2011, hearing, he admitted as much. The defense attorney and judge both noted that the contact was inappropriate.

But the intermediary called Wintory again, and he appeared to be evasive when his supervisors questioned him about how many times he had talked to her.

He was taken off the case, which was subsequently pleaded to second-degree murder.