Will technology be the death of history?

/I'm not a Luddite -- you're reading this online, after all, and you got here from Twitter or Facebook -- but I worry that technology will be the death of history.

Even in an era when we are bombarded with instant news reports and we chronicle every moment on Facebook and Instagram, taking selfies, noting how we feel and where we are eating and maybe even posting a photo of breakfast, lunch or dinner, it is only that: Of The Moment.

Where do those momentary chronicles go, who stores them, and who will view them a day, a week, a month, a century from now? What good will they do toward understanding who we were and why? And how many of them will just remain locked in last year’s machine, inaccessible to next year’s software?

In 2001, Laurence Bergreen published Over the Edge of the World, a fascinating book about Ferdinand Magellan's 16th Century voyage around the globe. Bergeen based the book largely on journal accounts by several of the explorers on Magellan's ships, which he found preserved in libraries in Madrid and Lisbon and Rome. They were first-person accounts that made the narrative real and relevant, illustrating the fund-raising and bureaucracy of getting the boats in the water, and the organizational hassle of dealing with hundreds of weary sailors who would rather have remained in the tropical paradises of the Caribbean among beautiful, naked and willing native women than pile back into leaky little boats to face scurvy and likely death. The fact that there were so many journalists among the sailors was in itself remarkable. The voyage took place at a time when few people knew how to read or write, and to have that many learned men aboard showed that the best and brightest had been sent forth for a scientific coup that had great political and economic import.

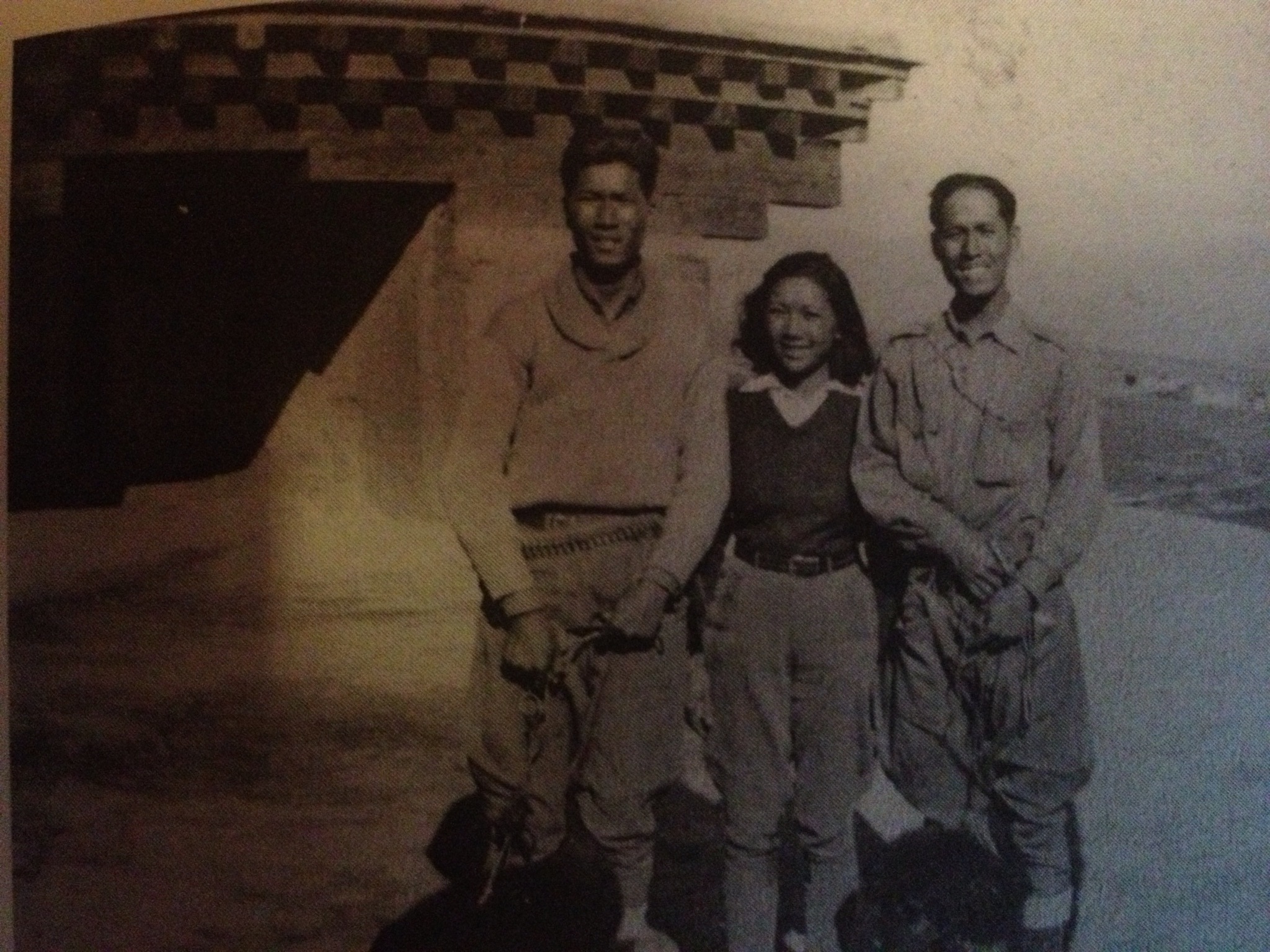

My 2002 book, Chasing the Panda, told the life stories of Quentin and Jack Young, Chinese-American brothers who were bring-'em-back alive hunters in China in the 1930s and who were instrumental in bringing the first giant panda out of China to the United States.

Both brothers were still alive in the 1980s, when I did the bulk of my research, but one was in his 70s and the other in his 80s. Not only did they have fading memories, but they fought with each other like jealous adolescents, each downplaying the other’s exploits.

But we would page through their photo albums together, and they would recall moments of fear or pleasure: a desperate night when they drew guns on each other in a blizzard in Sichuan; the time when they were guests of the princess of Kantze Sikong, a primitive tribeswoman in a bowler hat whom they dazzled with flashlights and other modern marvels; how they met the American socialite, Ruth Harkness, who almost made them famous, even as she made them miserable.

There was a wealth of letters that Jack and Quentin and their friends, employers and rivals had written to and about each other archived at The Field Museum in Chicago, The New York Museum of Natural History, The Bronx Zoo, and other places. I read them there and made copies which I later showed to the Young brothers to further jog their memories. Often, they had forgotten what they had written.

In the libraries at Northwestern and Arizona State Universities, I found old books and journals and magazines that chronicled their exploits when they were dashing young men, which helped fill in other lapses in their memories.

Who writes letters nowadays? The Young brothers and their associates and enemies had to, to keep in touch with their relatives and their bosses at the museums for which they collected. They had long hours out in the field to do so. Who keeps journals now?

I write emails and Tweets and Facebook posts. When I cover the Jodi Arias trial as a newspaper reporter, I don't even take notes. Instead, I narrate events on Twitter, then use those tweets and the feedback from my followers to put together online and newspaper stories. Where will those Tweets be in ten years?

Books are increasingly digital; the bookstores are closed. A disturbing 1996 New Yorker article described how the San Francisco Public Library had sent 200,000-some books to landfills to clear shelf space. The main criterion for disposal was whether the books had been lent out recently. I doubt anyone had checked out Trailing the Giant Panda by the sons of Theodore Roosevelt or Land of the Eye, books that I used for my research on Chasing the Panda. They would have been goners. Magazines? Journals? Likely replaced by blogs.

My photographs are no longer tangible images in boxes or albums. They are ephemeral pixels stored in my phone and my iPad, and hopefully most of them will still be floating in The Cloud in a year or two, when those gadgets fail. Other photos have already been turned into digital ghosts locked in desktop PCS that no longer work, backed up to CDs that broke or erased themselves and won't fit into any computer drives within a year or two, anyway.

Truth be told, I can't even access many of the materials I created while writing the Chasing the Panda. The manuscripts are buried in out-dated computers that no longer function, on floppy disks or diskettes or CDs that, if any data remains on them, can no longer be slotted into any modern machine. When I reissued the book in paperback in 2012, I still had the production CDs from the hard-cover edition, but the software had gone obsolete in those ten years, and my designer, Maria Radloff, had to search for someone who still had the old software in order to convert it to something compatible with what was current software two years ago.

As technology marches on, it leaves a trail of useless machines and irretrievable data.

How will future historians mine that data?

Or will we all just live in the moment and ignore history until we no longer realize that we are doomed to repeat it?

Quentin, Su Lin and Jack Young in Sichuan, 1934.