The Lion Hunter, Chapter One:

/It was six in the morning, and he’d barely slept because he knew she was coming. He had a good view of the valley from the little stoop outside the hired-help trailer at his dad’s ranch. The summertime grass was chest-high. The sun was just coming up and it had streaked the sky in layers of blue and pink and orange, fanned out like an Arizona state flag. A mile down the road he could see the cloud of dust dragging behind her pickup truck. There was a cup of coffee in his hand, but he wasn’t drinking much of it, because he really didn’t want to stay awake much longer than it would take to greet her and then drop into bed with her.

He was impatient, so it took forever for her pickup to wind up to the trailer. She slammed the door as she jumped out and rooted in the truck bed, tossing tools aside, until she found her green Army-surplus duffel bag. She was giggling, punchy silly, and he knew she’d driven all night to get there.

“Got off at midnight,” she said. “Wasn’t much more than a campfire that took off running. But since it was inside a campground, we just drove the engine right up to it and squirted it out. Easy stuff.”

She coughed a smoky firefighter’s cough

“What time did you get in?” she asked him.

“Let me put it this way,” he drawled. “It was so late when I got in that the only thing on ESPN was two white guys boxing.”

“That’s late.” She belly laughed.

It sounded like a joke, and it could have been, but honest to God, it was true. The Scottish featherweight championship: a couple of scrawny, tattooed guys with Brit names like Nigel and Barry and Graham flailing at each other.

They laughed as they hugged, and he ran his hand up her back inside her t-shirt. She smelled of grease and wood smoke. He could see soot behind her ears, as if she had just washed the front of her face in the dark in her hurry to get on the road.

She pushed his hand away.

“Let me get a shower first,” she said.

“I’ll be waiting in bed.”

He threw the last contents of his coffee cup out into the grass.

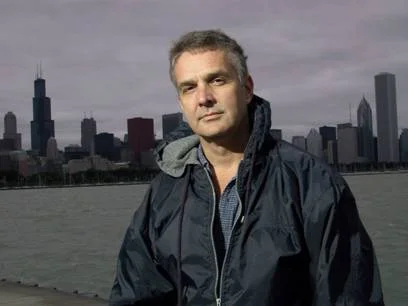

Lanny. His name was Lanny, Lanny Klegg, and he’d only known the girl for a couple of months, so he was still in those early stages where a soul can’t tell lust from love from some deeper ache, like grief.

He met her at a funeral, the funeral of his cousin John Peter, who no one ever called “John” or “Johnny,” but always “John Peter.” He was Lanny’s good friend and best playmate as a kid, his closest relative, not just in age, but because they were both “eccentrics,” as his dad put it. The Kleggs were an extended ranching family, but both of these boys had taken up with traditional ranching enemies. Lanny worked for “big government”--the Arizona Game and Fish Department--and John Peter was an environmental lawyer, a term whose very utterance could lower the temperature in any rural household--though he left the grazing lawsuits to his partner, Rock Robbins, and consequently, Robbins got so many threats from pissed-off ranchers that he sometimes wore a gun in a holster, same as they did.

Even folks who knew them both well never realized that John Peter and Robbins were more than just law partners. They were lovers. Both of them were just so big and ordinary in their demeanor that no one in town ever thought they were anything but a couple of divorced guys who were too busy or too clunky to meet women. And frankly, the townswomen were grateful for that.

John Peter and Robbins shared a dusty office in downtown Globe, full of books and papers and old dogs that padded up to every person that came in the front door. But they kept separate homes, partly to conceal their sexuality, but also because they’d both lived alone too long to suffer a roommate.

John Peter had battled melanoma for nearly ten years before it finally killed him. Though he’d had plenty of time to get used to the idea, Lanny was still so upset when John Peter died that he didn’t think he’d get through the funeral service. It was held under a big cottonwood tree next to John Peter’s home, a three-room cabin at scrub-oak elevations that, in contrast to his cluttered office, was so stark and simple as to be zen-like. The speakers had to shout to be heard over the sound of the creek nearby, but the running water was calming to Lanny, and so was listening to others talk about John Peter with as much respect and love as he felt his cousin deserved.

Outside the cabin, the neighbors, good country folk, had set up tables loaded with cold cuts and breads and pies and beans. Lanny held his Stetson hat in one hand at his side, though most of the other men and some of the women had worn theirs all through the service and as they sat to eat at the supper tables. He was leaning awkwardly against the side of the cabin trying to make small talk with some lady who wanted to tell him all about her bout with shingles when he heard the music.

It took a moment to figure out where it was coming from, Debussy, though he didn’t know that, “Clair de lune” on a piano, John Peter’s piano, a haunting tune on the sunniest of days, but achingly beautiful on that emotionally dark one, and Lanny followed it into the cabin.

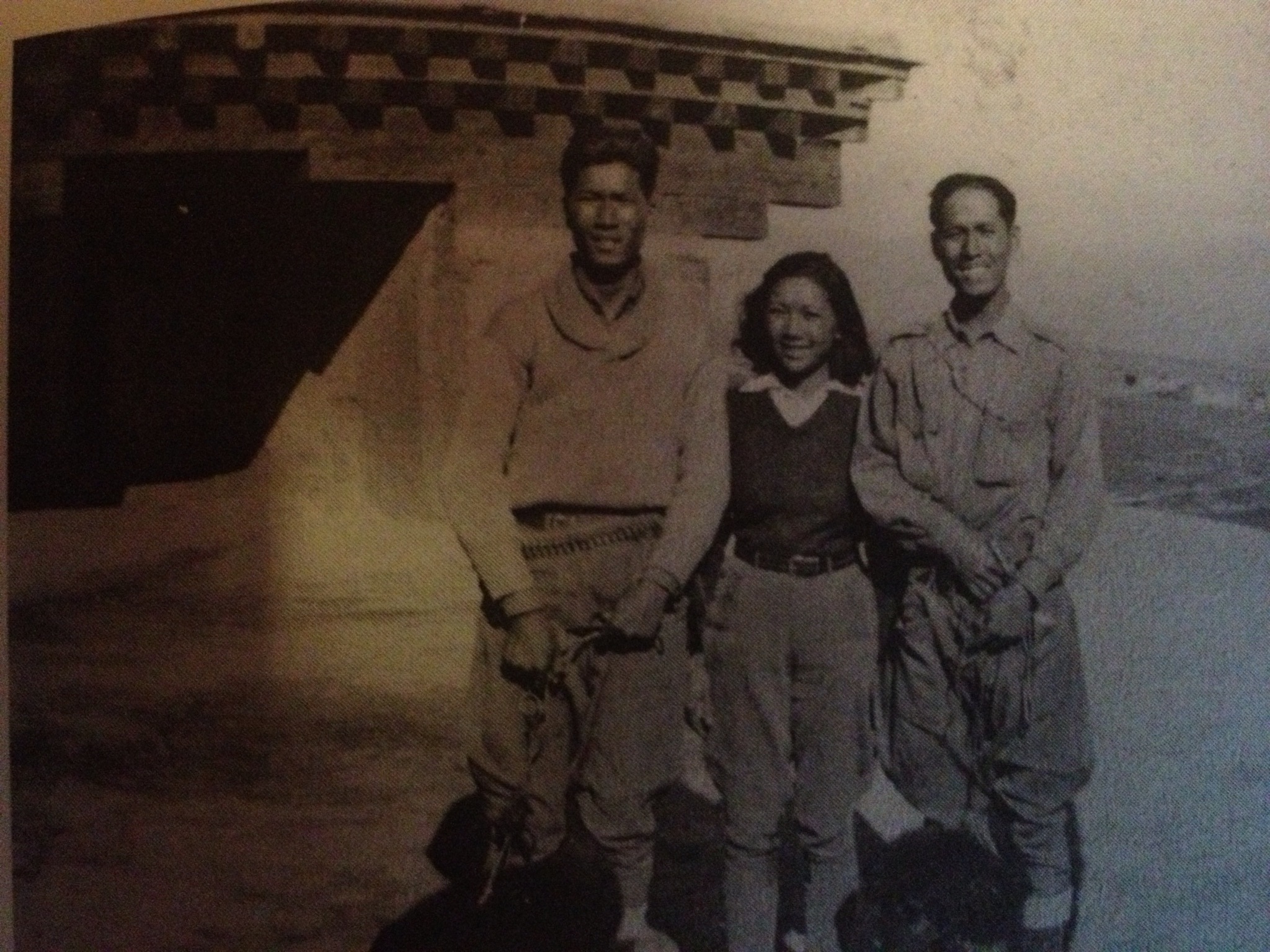

She was a vision in a sleeveless summer dress. The first thing he noticed was her arms, taut and beautifully turned, and he knew right away that the muscles came from hard work, not from standing in front of a mirror at the health club. She had long shiny dark hair, and darker eyes, which he noticed when she looked up to see who was there. He nodded. If he’d seen a picture of her, he might not have found her so pretty, but there was something radiating out of her that made her more attractive than anyone he’d met before. “What’s your name?” she said firmly without stopping playing.

“Lanny,” he said.

“That’s an unusual name,” she answered. She was smiling as if at a private joke, and it made Lanny feel like an embarrassed kid.

“Not around here,” he croaked out. “You must be from out east.”

“Sort of.”

“What’s your name?

“Frida.”

“We don’t have many of those out in these parts, either.”

“Good,” she chuckled, without looking up from the keyboard, and he felt his face heating up, sure now that she was making fun of him. The music echoed in the empty little room, filled its space, and trickled out through the cracks in the walls.

He wanted her to talk to him, but she was looking at the keys, wanted to talk to her, but couldn’t think of a damned thing to say. He was more than a little intimidated, not just by her beauty, but by the firmness in her gaze and the confidence in her voice. She must be smart, too, he figured, judging from the egghead music, and maybe that scared him most of all--scared him and excited him at the same time.

She didn’t even look back up, and he took that as a dismissal, muttered, “Nice to meet you, miss” in such a small voice that he barely heard it himself and walked out of the room--but not away. Outside the door, he listened until the last notes of the song lingered under the sustainer pedal and finally floated into the hot afternoon air. Then he quickly put his hat on and slipped off to his truck, which he’d had to park a good distance up the forest road because of the crowd of funeral goers, all the time hoping she didn’t see him and think he was some sort of eavesdropping peeper.

He turned his truck radio on and even that mocked him, a plaintive, melancholy song. The lyrics poked and prodded at every spot that hurt, like a massage in three-quarter time.

Baby, baby, I could call you baby,

if I weren’t so empty in the head and tied up in the tongue.

Baby, baby, I could call you baby,

if I weren’t so green and dumb.

“Green and dumb,” he said aloud to himself. “Ain’t that the truth.”

A week later he was up at a fire camp near the Grand Canyon. There had been a sizeable blaze, a couple thousand acres of ponderosa pine, and he was supposed to be on hand to answer questions about wildlife.

“Hey Lanny,” he heard a voice call out. It was a woman, her face black with soot around her goggles, her hair braided down her back and slipping out from under her helmet. He recognized the arms coming out of a rolled up t-shirt; she was shouldering that long-handled pickax they call a Pulaski, and he suddenly realized how she built those muscles.

“Shit, it’s Frida,” one of the other firefighters cracked. “Hard to tell her from that Pulaski. Both of them got a hatchet on one end and a hoe on the other. Get it?”

“Yeah, I get it asshole--not that you ever will, and that’s your loss,” she barked. Immediately turning toward Lanny she said, “See what I put up with?” and he could tell by her voice that she didn’t find it funny.

They talked for a minute or two, and then both had to get to work. She took the pen from his shirt pocket, grabbed his clipboard, wrote her phone number on a corner of his field notes, and told him to call her if he was ever in Flagstaff. He usually went there a few times a month, but of course, once he had personal reasons to go, his work kept him locked in his office in Phoenix for weeks. He wanted a real reason to be in Flagstaff, just in case her invitation had been one of those things people say, like about having lunch--someday, maybe never.

It was on his mind, and he found himself talking to John Peter about it—sort of. John Peter had been cremated, and he’d asked Lanny to spread his ashes, somewhere—though he died before he could tell Lanny just where. So they sat in a box on Lanny’s dresser. Lanny was a bit self-conscious about this, and he found himself making apologies out loud to his cousin as to not knowing what to do with him. It was a short step from there to saying “good morning” and “good night” and uttering greetings when he was passing through the room. At times he felt just a bit nuts, but it seemed to ease the pain of losing a best friend, who, in a way, was still there.

So he was combing his hair in the mirror one morning, hovering over the ashes and thinking about Frida in Flagstaff, when he thought he could hear John Peter’s voice in his head, saying what he always said: “Go on up, Lanny. Buy a bad hat. Get drunk and walk around. It’ll do you a world of good.”

So he worked up the nerve to call her, told her he’d be in town one night and did she want to meet for a beer or something. He was startled at how quickly she said yes. They agreed to meet Sunday night at a country-music dancehall on Route 66.

He got to town early, so after he checked into a dowager hotel downtown, he drove up to the ski area to waste time, then walked out one of the hiking trails that fan out from the parking lots. A mile in, he found a fallen tree at the uphill end of a meadow--no more than a glade, really--but with enough space between the big Douglas firs that he could watch the sun go down. Then, as it got dark, he hiked back out, went back to his room and showered.

It was still early, but he went to the bar anyway, and sat, anxious as a schoolboy on a first date, scrutinizing each woman who came in the door, worried he might not recognize her. He was looking so hard that he didn’t see her. She walked up from the other direction and punched him on the arm, the way a guy might punch another guy in a high school gym class.

That was the only masculine thing about her. She was wearing a black t-shirt and tight jeans and black cowboy boots. Her hair was just as loose and shiny as he remembered. She didn’t seem to be wearing any makeup at all, and didn’t seem to need any, the way she glowed. He could feel the energy radiating out of her, tingly, wild and curious at the same time, like a young horse, and he worried that if he moved too fast, he’d spook her, and she’d gallop away before he got close enough to slip a rope over her neck.

The bar was loud, the music louder, and that was a relief to him, because he was as tongue-tied as he’d been at John Peter’s funeral. She pulled him out to the dance floor, and that was fine, too, because it kept him from having to speak. He knew enough about dancing to let the woman do what she wanted while standing there, appearing to lead.

As the bar cleared, he walked her to her truck and bent down for a formal little peck on the lips. She snickered. He blushed and said goodnight--then beat himself up all the way back to his hotel. He had a grim little room, not much more than a rickety bed frame, a chair and a TV set, which he turned on, hoping for the news.

“Lanny.” He heard his name, from outside. “Lanny,” a woman’s voice calling as if she were lost.

He opened the window and stuck his head out. She was down on the sidewalk, her arms wrapped around herself. He got a big knot in his stomach.

“I’m freezing,” she said when she saw him peering out. “What room are you in?”

A moment later she was at the door.

“Sorry,” she said. “I’m too drunk to drive back to my place. Can I stay here until I sober up?”

Of course she could, in his wildest dreams. He stepped aside to let her in, almost stumbling over his own feet.

“I’m freezing, Lanny,” she said, a bit more insistent. “Do you have something warm I can put on?”

He rooted in his valise and pulled out a flannel shirt. She peeled off her t-shirt, and then struggled with the inside-out sleeves of the shirt he’d just given her. Lanny wondered why she just didn’t put it on over the t-shirt--but only for a second, because he was gawking at her. Her abdomen was as tight as her biceps. Her breasts weren’t large, but they were fuller than he expected, welling up out of a black lace bra with her breathing. He wanted to explore every inch of her body with every inch of his.

She felt his gaze and looked up with an embarrassed expression and said “Sorry,” as she pulled the shirt on and buttoned it.

“Sorry for what?”

She looked a bit exasperated.

“Lanny,” she said. “I’m starting to wonder if you’re some kind of a homo. What the hell do I have to do to get you to make a pass at me?”

“Christ,” he thought, “here she is, waving me on, like the guy at the airport with those big orange things guiding the plane into the gate, and I’m trying so fucking hard to be a gentleman, that I can’t even see her.”

He put his arms around her and kissed her the way he should have kissed her when they were standing in the bar parking lot, and he couldn’t remember much of what happened next. It was an out-of-body experience, detached, a sudden coming to, looking up at her face--her eyes closed forcefully, her jaw set, like she was working hard to focus every bit of her strength and energy on where they were joined together at the pelvis. Her lithe body was rocking fast and rhythmically, and he suddenly realized that with her every thrust, the headboard banged hard against the wall, and everyone in the building would wake up and hear the drumbeat of their lust. But so what? He surrendered to her right then and there.

From the trailer’s bedroom window, Lanny could see the width of the valley. The mountains in the distance were on the other side of the Mexican border, maybe 20 miles south. In this part of Arizona, the border itself was just a barbed-wire fence that cut through a pasture. A hundred years ago, the ranches used to straddle the line; people and cattle crossed at will. But that had ended with Arizona’s statehood early in the 20th century. Mexico took its lands away from the families that had already ranched them for generations. Now, it was still easy to cross over, but to go where? The Mexican federales camped in their trucks just a mile or so down the dirt roads that went from one nation to the next, relicts of that earlier time. You didn’t want to tangle with those boys, machine-gun-toting youngsters, some of them. And back then, not many Mexicans tried to sneak into this part of Arizona. The mountains were too high, the expanses too great.

Lanny suddenly realized that the shower had turned off and he shifted to watch her come out of the bathroom, still glistening, her hair wrapped in one towel, her torso in another. She rooted through his valise and pulled out the same flannel shirt she’d borrowed on the night they first slept together. When she dropped the towel around her, he caught a quick glimpse of the long lines of her waist as it curved into her hips.

She buttoned about half of the shirt buttons and then slid into bed next to him, her back, her legs, the length of her body warm and silky. He ran his hand up her thigh, along her waist, working his fingers up the knot of muscle next to her spine.

She was already breathing deeply, and he realized she’d fallen asleep. But she had a smile on her face, and so he left her alone, and within minutes, he was asleep, too.